OF THE BEAVER TRIBE*.

Belonging to the present tribe, there are but two species that have hitherto been discovered, the Common and the Chili Beavers; and even of these, it seems doubtful whether the latter ought not to be arranged with the Otters.

THE COMMON BEAVER t.

There is reason to suppose that this animal was once an inhabitant of Great Britain; for Giraldus

* The Beavers have the front teeth in their upper jaw truncated, and excavated with a transverse angle; and those of the lower jaw are transverse at the tips. There are four grinders on each side. The tail is long, depressed, and scaly; and there are collar-bones in the skeleton.

f Description. The general length of the Beaver i» Cambrensis says, that Beavers frequented the river Tievi in Cardiganshire, and that they had, from the Welsh, a name signifying "the Broad-tailed animals." Their skins were valued by the Welsh laws, in the tenth century, at the enormous sum of a hundred and twenty pence each; and they seem to have constituted the chief finery and luxury of those days. Beavers are at present natives of most of the northern parts of Europe and Asia, but are principally found in North America.

No other quadrupeds seem to possess- so great a degree of natural sagacity as these. Yet when we consider that their history, as hitherto detailed, has been principally taken from the reports of the Beaver-hunters, whose object it is, not to study the nature or manners of the animals, but merely to seize upon them as articles of commerce, and whose accounts are often in themselves contradictory, it 'is necessary that we should not give implicit faith to every thing that has been written, even by the most respectable authors, concerning them, where these authors have not themselves witnessed the facts they relate. Captain George Cartwright, who resided fourteen years on the coast of Labrador, in order to collect the different furs of that dreary climate, saw more of the manners of the Beaver, than most other writers. To his work, therefore, and to that of M. du Pratz, who, in Louisiana, was an eye-witness

about three feet. The tail is oval, nearly a foot long, and compressed horizontally,-but rising into a convexity on its upper surface: it is destitute of hair, except at the base, and is marked into scaly divisions, like the skin of a fish. The hair of the Beaver is fine, smooth, glossy, and of a chestnut colour, varying sometimes to black; and instances have occurred in which these animals have been found white, cream-coloured, or spotted. The ears are short, and almost hidden in the fur.

Svnonyms. Castor Fiber. Linn—Castor. Buffotu— Shatt's Gen. Zoo'. Pl 128 Bca. Quad. 417.

to their labours, I have principally had recourse, in endeavouring to give to the reader as faithful an account as possible of the habits of life and economy of these, wonderful animals.

Beavers generally live in associated communities, consisting of as many as two or three hundred individuals; and they inhabit extensive dwellings, which they raise to the height of six or eight feet above the surface of the water. They select, if possible, a large pond; in which they raise their houses on piles, forming them either of a circular or oval shape, with arched tops, and thus giving them, on the outside, the appearance of a dome, while within they somewhat resemble an oven. The number. of houses is, in general, from ten to thirty. If the animals cannot find a pond to their liking, they fix on some flat piece of ground, with a stream running through it; and in making this a suitable place for their habitations, a degree of sagacity and intelligence, of intention and memory, is exhibited, which approaches, in an extraordinary degree, to the faculties of the human race.

Their first object is, to form a dam. To do this, it is necessary that they should stop the stream, and of course that they should know in which direction the water runs. This seems a very wonderful exertion of instinct; for they always do it in the most favourable place for their purpose, and never begin at a wrong part.. They drive stakes, five or six feet long, into the ground, in different rows, and interweave them with branches of trees; filling them up with clay, stones, and sand, which they ram so firmly dow'n, that though the dams are frequently a hundred feet long, Capt. Cartwright says, he has walked over them with the greatest safety. These are ten or twelve feet thick at the base, and gradually diminish towards the top, which is seldom more than two or three feet across. They are exactly level from end to end; perpendicular towards the stream; and sloped on the outside, where grass soon grows, and l enders the earth more united.■

The houses are constructed, with the utmost ingenuity, of earth, stones, and sticks, cemented together, and plastered ,in the inside with surprising neatness. The wijlls are about two feet thick; and the floors so much higher than the surface of the water, as always to prevent them from being flooded. Some of the houses have only one floor; others have three. The number of Beavers in each house is from two to thirty. These sleep on the floor, which is strewed with leaves and moss; and each individual is said to have its own place. When they form a new settlement, the animals begin to build their houses in the summer; and it costs them a whole season to finish the work, and lay in their winter provisions: these consist principally of bark and the tender branches of trees, cut into certain lengths, and piled in heaps under the water.

The houses have each no more than one opening, which is under the surface of the water, and always below the thickness of the ice. By this means they are secured from the effects of frost.

The Beavers seldom quit their residence unless they are disturbed, or their provisions fail. When they have continued in the same place three or four years, they frequently erect a new house annually; but sometimes merety repair their old one. It often happens that they build a new house so close to their former dwelling, that they cut a communication from one to the other; and this may have given rise to the idea of their having several apartments.

During the summer-time, they quit their houses, and ramble about from place to place, sleeping under the covert of bushes, near the water-side. On the feast noise, they betake themselves into the water for security; and they have sentinels, who, by a certain cry, give notice of the approach of danger. In the winter they never stir out, except to their magazines under the water; and during that season they become excessively fat.

In one of his excursions into the northern parts of Louisiana, M. du Pratz (who resided sixteen years in that country) gives us an account of a colony of Beavers, to many of whose operations he was himself a witness. But this, in some respects* appears contradictory to the account of Captain Cartwright.

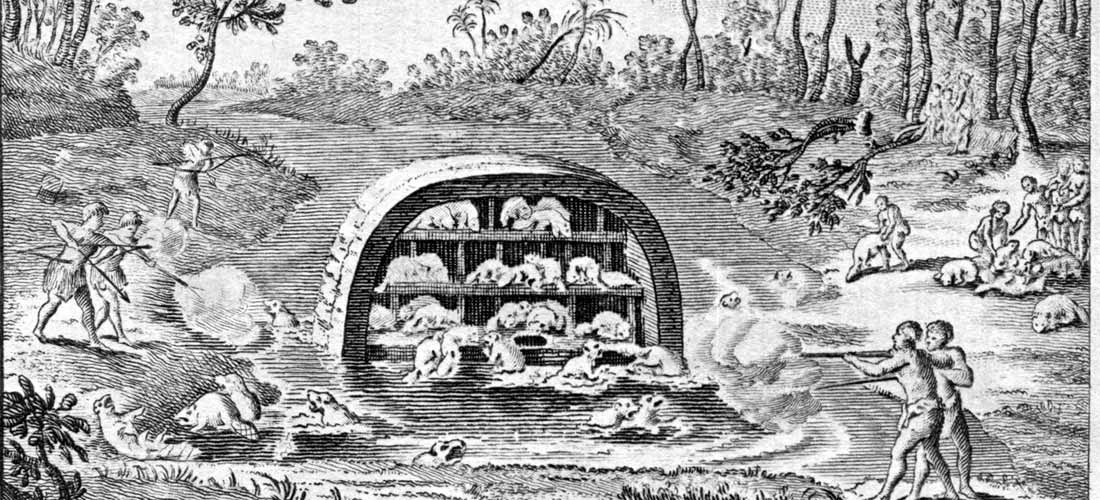

At the head of one of the rivers of Louisiana, in a very retired place, M. du Pratz found a Beaver dam." Not far from it, but hidden from the sight of the animals, he and his companions erected a hut, in order to watch the operations of these animals at leisure. They waited till the moon shone bright; and then, carrying in their hands branches of trees, in order to conceal themselves, they went with great care and silence to the dam. M. du Pratz ordered one of the men to cut, as silently as-possible, a gutter, about a foot wide, through it; and to retire immediately to the hiding-place.

"As soon as the water through the gutter began to make a noise (says this writer) we heard a Beaver come from one of the huts and plunge in. We saw him get upon the bank, and clearly perceived that he examined it. He then, with all his force, gave four distinct blows with his tail; when immediately the whole colony threw themselves into the water, and went to the dam. As soon as they were assembled, one of them appeared, by muttering, to issue some kind of orders; for they all instantly left the place, and went out on the banks of the pond in different directions. Those nearest to us were between our station and the darri, and therefore we could observe their operations very plainly. Some of them formed a substance resembling a kind of mortar; others carried this on their tails, which served as sledges for the purpose. I observed that they ranged themselves two and two, and that each animal of every couple loaded1 his fellow. They trailed the mortar,

which was pretty stiff, quite to the dam, where others were stationed to take it; these put it into the gutter, and rammed it down with blows of their tails.

"The noise of the water soon ceased, and the breach was completely repaired. One of the Beavers then struck two blows with his tail; and instantly they all took to the water without any noise, and disappeared."

M. du Pratz and his companions afterwards retired to their hut to rest, and did not again disturb the animals till the next day. In the morning, however, they went to the dam, to see its construction; for which purpose it was necessary that they should cut part of it down. The depression of the water in consequence of this, together with the noise they made, roused the Beavers again. The animals seemed much agitated; and one of them, in partitular, was observed several times to approach the labourers, as if to examine what passed. As M. du Pratz apprehended that they might run into the woods, if further disturbed, he advised his companions again to conceal themselves.

"One of the Beavers (continues our narrator) then ventured to go upon the breach, after having several times approached and returned like a spy. He surveyed the place, and, with his tail, struck four blows, as he had done the preceding evening, with his tail. One of those that were going to work, passed close by me; and as I wanted a specimen to examine, I shot him. The noise of the gun made all the rest scamper off with greater speed than a hundred bjows of the tail of the overseer could have done." By firing at them several times afterwards, the animals were compelled to run with precipitation into the woods. M. du Pratz then examined their habitations.

Under one of the houses he found fifteen pieces of wood; with the bark in part gnawed off, apparently intended for food. And, round the middle of this house, which formed a passage for the Beavers to go in and out at, he observed no fewer than fifteen different cells.

Beavers produce their young-ones towards the end of Junes and generally have two at a time. These continue with their parents till they are three years old, when they pair off, and form houses for themselves. If, however, they are undisturbed, and have plenty of provisions, they remain with the old ones, and thus form a double society.

Instances have occurred of Beavers having been domesticated. Major Roderfort, of New York, related to Professor Kalm, that, for a year and a half, he had in <his house a tame Beaver, which was suffered to run about like a dog. The Major gave him bread; and sometimes fish, of which he was very greedy. As much water was put into a bowl as he wanted. AH the rags and soft things he could lay hold off, he dragged into the corner where he was accustomed to sleep, and made a bed of them. The cat in the house, having kittens, took possession of his bed; and he did not attempt to interrupt her. When the cat went out, the Beaver often took one of the kittens between his paws, and held it to his breast to warm it, and seemed to dote upon it: as soon as the cat returned, he always restored to her the kitten. Sometimes he grumbled; but never attempted to bite.

In the year 1820, there were in the upper room at Exeter 'Change, London, two Beavers, which had been there some time. They were very tame, and would suffer themselves to be handled by the visitors; but most persons were alarmed, ton approaching them, by the animals uttering their weak and plaintive cry. This noise they also frequently emitted during their play with each other. At times they were exceedingly gay rtnd frolicsome, wrestling and playing with each other, as far as the limits of their small apartment would admit. They often sate upright to look about them, or to eat; and, if any thing moveable was given them to play with, they would drag it about, and seem highly pleased with it. They were in no instance observed to drag any thing about on their tails, or to make any attempts to do so. In all their manners these animals were extremely cleanly. They were fed with the bark of trees, and on bread; and such was their propensity to gnaw wood, that it was not considered safe, notwithstanding the natural gentleness of their disposition, to allow them, the full range of a room, for they would soon have eaten their way out, and escaped.

The skin of the Beaver has hair of two kinds: that immediately next to the skin, is short, implicated together, and as fine as down; the upper hair grows more sparingly, and is both thicker and longer. The former is of little value; but the flix or down is wrought into hats, stockings, caps, and other articles of dress.

The skins of Beavers form a considerable article of traffic, both with the northern countries of Europe and with America. About fifty-four thousand have been sold by the Hudson's Bay Company at one sale: and in the year 17SJ8, one hundred and six thousand skins were collected in Canada, and sent into Europe and China. Those of a black colour are preferred, particularly such as are taken during winter.

The medicinal substance called castor is produced in what are called the inguinal giands of these animals; and each individual, both male and female, has usually about two ounces. That produced by the Russian Beavers is more valuable, and sells at a much higher price, than what is imported from America. The flesh is good eating.

It frequently happens that single Beavers live separate from the gener.il community, in holes, which, they make in the banks of rivers, considerably under the surface of the water, working their way upward to the height of many feet. These are called by the hunters Hermits, or Terrier Beavers. Like the rest, they lay up a store of provisions for the winter. It is supposed by Captain Cartwright, that their separation from society originates in attachment and fidelity; that, having by some accident lost their mate, they will not readily pair again. Whatever may be the causes, it has been remarked, that they have invariably a black mark on the skin of their backs; this is called a saddle, and by it they are easily distinguished from the others.