Giraldus Cambrensis (* 1146 in Manorbier Castle in Pembrokeshire; † 1223 in Lincoln), walisisch Gerallt Cymro, mehr bekannt unter der deutschen Übersetzung seines lateinischen Namens, Gerald von Wales, war ein cambro-normannischer Adliger. Er war Archidiakon, zugleich aber auch Schriftsteller, Diplomat, Kirchenpolitiker, Historiker, Volkskundler und Dichter.

The itinerary through Wales : and The description of Wales (by Giraldus Cambrensis

London, J.M Dent 1908

CHAPTER III

OF THE RIVER TEIVI, CARDIGAN, AND EMELYN

The noble river Teivi flows here, and abounds with the

finest salmon, more than any other river of Wales ; it has

a productive fishery near Cilgerran, which is situated on

the summit of a rock, at a place called Canarch Mawr, 2

the ancient residence of St. Ludoc, where the river, fall-

ing from a great height, forms a cataract, which the

salmon ascend, by leaping from the bottom to the top of

a rock, which is about the height of the longest spear, and

would appear wonderful, were it not the nature of that

species of fish to leap: hence they have received the

name of salmon, from salio. Their particular manner of

leaping (as I have specified in my Topography of Ireland)

is thus : fish of this kind, naturally swimming against the

1 On the Cemmaes, or Pembrokeshire side of the river Teivi,

and near the end of the bridge, there is a place still called Park y

Cappel, or the Chapel Field, which is undoubtedly commemora-

tive of the circumstance recorded by our author.

2 Now known by the name of Kenarth, which may be derived

from Cefn y garth the back of the wear, a ridge of land behind

the wear.

course of the river (for as birds fly against the wind, so

do fish swim against the stream), on meeting with any

sudden obstacle, bend their tail towards their mouth,

and sometimes, in order to give a greater power to their

leap, they press it with their mouth, and suddenly free-

ing themselves from this circular form, they spring with

great force (like a bow let loose) from the bottom to

the top of the leap, to the great astonishment of the

beholders. The church dedicated to St. Ludoc, 1 the mill,

bridge, salmon leap, an orchard with a delightful garden,

all stand together on a small plot of ground. The Teivi

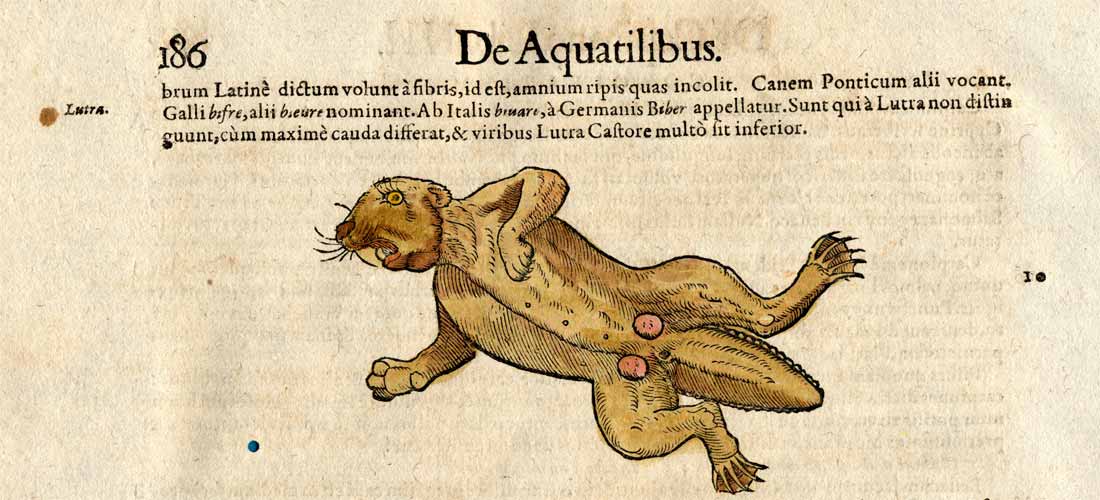

has another singular particularity, being the only river

in Wales, or even in England, which has beavers ; 2 in

Scotland they are said to be found in one river, but are

very scarce. I think it not a useless labour, to insert a

few remarks respecting the nature of these animals;

the manner in which they bring their materials from the

woods to the water, and with what skill they connect

them in the construction of their dwellings in the midst

of rivers; their means of defence on the eastern and

1 The name of St. Ludoc is not found in the lives of the saints.

Leland mentions a St. Clitauc, who had a church dedicated to

him in South Wales, and who was killed by some of his companions

whilst hunting. " Clitaucus Southe-Walliae regulus inter venan-

dum a suis sodalibus occisus est. Ecclesia S. Clitauci in Southe

Wallia." Leland, Itin., torn. viii. p. 95.

2 The Teivy is still very justly distinguished for the quantity

and quality of its salmon, but the beaver no longer disturbs its

streams. That this animal did exist in the days of Howel Dha

(though even then a rarity), the mention made of it in his laws,

and the high price set upon its skin, most clearly evince; but if

the castor of Giraldus, and the avanc of Humphrey Llwyd and

of the Welsh dictionaries, be really the same animal, it certainly

was not peculiar to the Teivi, but was equally known in North

Wales, as the names of places testify. A small lake in Mont-

gomeryshire is called Llyn yr Afangc; a pool in the river Conwy,

not far from Bettws, bears the same name, and the vale called

Nant Ffrancon, upon the river Ogwen, in Caernarvonshire, is

supposed by the natives to be a corruption from Nant yr Afan

cwm, or the Vale of the Beavers. Mr. Owen, in his dictionary,

says, " That it has been seen in this vale within the memory of

man." Giraldus has previously spoken of the beaver in his Topo-

graphy of Ireland, Distinc. i. c. 21.

western sides against hunters ; and also concerning their

fish-like tails.

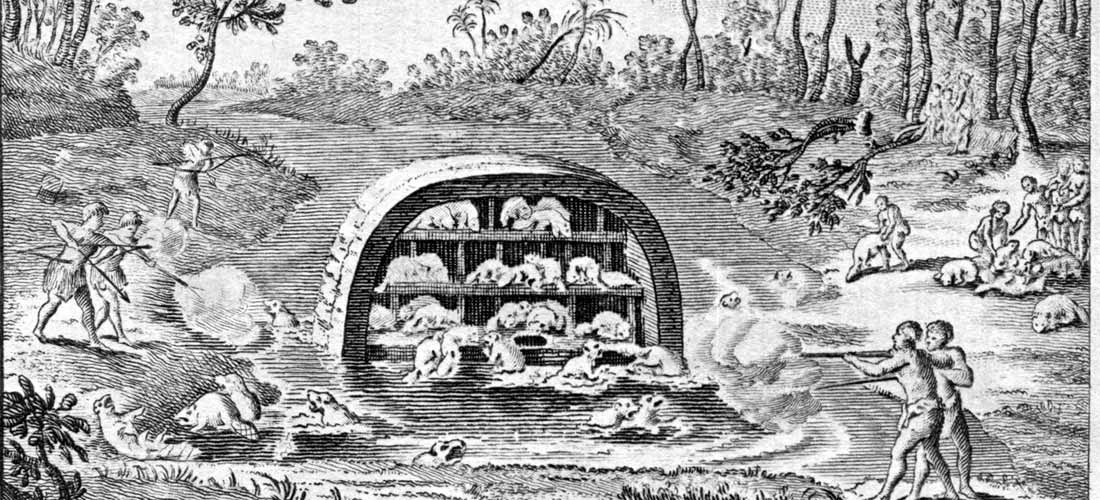

The beavers, in order to construct their castles in the

middle of rivers, make use of the animals of their own

species instead of carts, who, by a wonderful mode of

carriage, convey the timber from the woods to the rivers.

Some of them, obeying the dictates of nature, receive on

their bellies the logs of wood cut off by their associates,

which they hold tight with their feet, and thus with

transverse pieces placed in their mouths, are drawn along

backwards, with their cargo, by other beavers, who

fasten themselves with their teeth to the raft. The

moles use a similar artifice in clearing out the dirt from

the cavities they form by scraping. In some deep and

still corner of the river, the beavers use such skill in the

construction of their habitations, that not a drop of

water can penetrate, or the force of storms shake them;

nor do they fear any violence but that of mankind,

nor even that, unless well armed. They entwine the

branches of willows with other wood, and different kinds

of leaves, to the usual height of the water, and having

made within-side a communication from floor to floor,

they elevate a kind of stage, or scaffold, from which they

may observe and watch the rising of the waters. In

the course of time, their habitations bear the appear-

ance of a grove of willow trees, rude and natural without,

but artfully constructed within. This animal can re-

main in or under water at its pleasure, like the frog or

seal, who shew, by the smoothness or roughness of their

skins, the flux and reflux of the sea. These three

animals, therefore, live indifferently under the water, or

in the air, and have short legs, broad bodies, stubbed

tails, and resemble the mole in their corporal shape. It

is worthy of remark, that the beaver has but four teeth,

two above, and two below, which being broad and sharp,

cut like a carpenter's axe, and as such he uses them.

They make excavations and dry hiding places in the

banks near their dwellings, and when they hear the

stroke of the hunter, who with sharp poles endeavours to

penetrate them, they fly as soon as possible to the de-

fence of their castle, having first blown out the water

from the entrance of the hole, and rendered it foul and

muddy by scraping the earth, in order thus artfully to

elude the stratagems of the well-armed hunter, who is

watching them from the opposite banks of the river.

When the beaver finds he cannot save himself from the

pursuit of the dogs who follow him, that he may ransom

his body by the sacrifice of a part, he throws away that,

which by natural instinct he knows to be the object

sought for, and in the sight of the hunter castrates him-

self, from which circumstance he has gained the name

of Castor; and if by chance the dogs should chase an

animal which had been previously castrated, he has the

sagacity to run to an elevated spot, and there lifting up

his leg, shews the hunter that the object of his pursuit is

gone. Cicero speaking of them says, " They ransom

themselves by that part of the body, for which they are

chiefly sought." And Juvenal says,

"Qui se Eunuchum ipse facit, cupiens evadere damno

Testiculi."

And St. Bernard,

" Prodit enim castor proprio de corpore velox

Reddere quas sequitur hostis avarus opes."

Thus, therefore, in order to preserve his skin, which is

sought after in the west, and the medicinal part of his

body, which is coveted in the east, although he cannot

save himself entirely, yet, by a wonderful instinct and

sagacity, he endeavours to avoid the stratagems of his

pursuers. The beavers have broad, short tails, thick,

like the palm of a hand, which they use as a rudder in

swimming ; and although the rest of their body is hairy,

this part, like that of seals, is without hair, and smooth;

upon which account, in Germany and the arctic regions,

where beavers abound, great and religious persons, in

times of fasting, eat the tails of this fish-like animal, as

having both the taste and colour of fish.

We proceeded on our journey from Cilgerran towards

Pont-Stephen, 1 leaving Cruc Mawr, i.e. the great hill,

near Aberteivi, on our left hand. On this spot Gruffydd,

son of Rhys ap Tewdwr, soon after the death of king

Henry I., by a furious onset gained a signal victory

against the English army, which, by the murder of the

illustrious Richard de Clare, near Abergevenny (before

related), had lost its leader and chief. 2 A tumulus is to

be seen on the summit of the aforesaid hill, and the in-

habitants affirm that it will adapt itself to persons of all

stature ; and that if any armour is left there entire in the

evening, it will be found, according to vulgar tradition,

broken to pieces in the morning.

1 Our author having made a long digression, in order to intro-

duce the history of the beaver, now continues his Itinerary.

From Cardigan, the archbishop proceeded towards Pont-Stephen,

leaving a hill, called Cruc Mawr, on the left hand, which still

retains its ancient name, and agrees exactly with the position

given to it by Giraldus. On its summit is a tumulus, and some

appearance of an intrenchment.

2 In 1135.